MORE FROM SCOTLAND MAGAZINE

The Kings of Scotland: Balliol vs Bruce

From John Balliol to Robert the Bruce: here we look at four of the most complex medieval Kings of Scotland

The years from 1290 to 1371 witnessed a tumultuous tussle for Scotland’s throne between two distinct branches of the same extended family. From the first interregnum, known as the Great Cause, to the demise of the House of Bruce, which opened the door to the House of Stewart, here we look at four of the most complex medieval Kings of Scotland.

The Great Cause

In 1290, the House of Dunkeld, which had ruled Scotland for just over 250 years, came to an end with the death of Margaret, Maid of Norway, the young granddaughter of Alexander III of Scotland. With no heir, a succession crisis brewed.

Over two years, various claimants put their names forward, but no agreement could be reached and the English King Edward I (aka Edward Longshanks and the self-titled Hammer of the Scots) took charge of the process.

Of the 13 candidates who put their names to the court for consideration as Kings of Scotland, two had the strongest claims as descendants of David, the brother of William I who had ruled between 1165 and 1214. These were John Balliol, the grandson of David’s eldest daughter, and Robert Bruce, the son of David’s second daughter.

The court consisted of 104 auditors, 40 chosen by Balliol, 40 by Bruce and 24 by Edward I. As Timothy Venning writes in his book The Kings & Queens of Scotland, “Edward …decided to require all the candidates to recognise him as the overlord and required custody of all the royal castles in Scotland.” These were conditions Bruce could not swallow but which the more malleable Balliol did. As such, he pledged fealty to Edward and was proclaimed King of Scots in 1292.

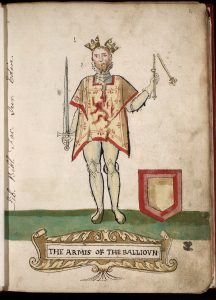

John Balliol

As the Scottish monarch of choice of the English king, it’s perhaps unsurprising that King John’s reign was both short and somewhat ignominious. He ruled for just four years during which time Edward became more aggressive in his assertions over Scotland.

The final straw came in 1294 when Edward demanded that Scotland send troops to aid in his war with the French. Influential Scots, tired of Edward’s interference and John’s weaknesses, created a council of nobles and clergymen who ruled in John’s name.

They then formed a treaty with Philip IV of France against the English, kicking off the ‘Auld Alliance’.

Now only nominally in charge, John renounced his fealty to Edward in 1296, which spurred Edward to march his army north, where he defeated the Scots at the Battle of Dunbar and subsequently took several castles, including Edinburgh and Stirling.

John surrendered to Edward in Angus and was forced to sign a humiliating confession. Having proved to be ineffective to both sides, he was forced to abdicate in 1296. He was imprisoned in the Tower of London until 1299, when he was allowed to live in exile in France, where he stayed until his death in 1313.

Perhaps his most enduring legacy as one of the Kings of Scotland came when, following Edward’s victory, the English took the Stone of Destiny from Scone to Westminster Abbey where it remained until 1996.

The First War of Scottish Independence

King John’s abdication and Edward’s relentless forays into Scotland left the country without a monarch for a decade until 1306. This was the period of now-Hollywood fame when countless battles and guerrilla-like campaigns were fought in a bid for Scottish sovereignty and the country was governed by a series of guardians, including William Wallace.

Robert the Bruce

Enter one of the most eulogised Kings of Scotland, Robert the Bruce. Grandson of Robert Bruce who stood against King John in 1292, the man who would be king was a strong and able leader and a mighty warrior with a deep-rooted commitment to seeing a legitimately independent kingdom of Scotland. This even saw him fighting alongside the English for a brief period when King John revolted.

His early reign was mired in scandal as he was believed to have brutally murdered John Comyn III, a joint guardian and rival, in a Dumfries church. While he was swiftly crowned in 1306, he was then excommunicated by the Catholic church.

Overall, Robert I was an effective king, continuously moving against Edward I and, subsequently, Edward II, from 1307. Said to have been a pious man, he kept himself busy with campaigns in Ireland, endless borderland raids and nurturing national identity while dealing with issues such as famine and disease.

He inadvertently sowed the seeds of future discontent by confiscating the lands of those who backed John and Comyn and distributing them among his supporters. The ‘disinherited’ barons would not forget.

Of course, Robert’s great victory, the 1314 Battle of Bannockburn, is the stuff of legend, while the 1320 Declaration of Arbroath, which united numerous members of the nobility in a bid to seek papal recognition, remains one of Scottish history’s most fascinating documents.

Bruce ruled for 23 years and finally saw his dreams of papal recognition and peace with England come to life in 1328, just before his death, likely from leprosy, in 1329. According to Royal.uk, when he died, Robert the Bruce had achieved “all he had fought for: ejecting the English, re-establishing peace and gaining recognition as the true king.”

David II

When Robert I died, his young and only surviving son by his second wife, David, was just five – seven when finally crowned in 1331. Thanks to the papal edict received in 1328, David became the first Scottish king to be anointed.

All was not well, however. The ‘disinherited’ barons and Edward II’s successor, Edward III, were waiting in the wings to usurp the young king and place Edward Balliol, son of King John, on Scotland’s throne.

In 1333, Edward III defeated the Scots near Berwick, and David was evacuated to France where he stayed until 1341 when he was able to return and take control of Scotland, aged just 17. In 1346, he rather unsuccessfully invaded England in defence of his French ally; he was captured and held in the Tower of London and then Windsor Castle for some 11 years.

In his absence, his nephew Robert Stewart acted as regent (put a pin in him, he’ll be back). David eventually returned home in 1357 to a disgruntled people sick of the high taxes needed to pay his ransom.

In a bid to cancel his ransom debt, David rashly offered Scotland up whole to Edward, fully aware that this would never be sanctioned in the Scottish Parliament. There was, however, a legitimate issue of succession as David had no heirs, and his tighter ties with Edward infuriated many nobles in Scotland.

Venning asserts that while “contemporaries paid tribute to his bravery and his tenacious pursuit of his rights,” his “reputation is still much lower than that of his father. He cannot be called gifted or successful. But he was determined; his reputation may have stood higher had he reigned for longer and left children.”

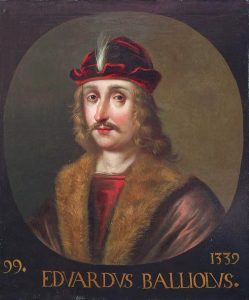

Edward Balliol

The final player in a game of cat and mouse, Edward Balliol’s time in the spotlight jig-sawed around that of David II. Following his father King John’s abdication in 1296, Edward spent time exiled in France. While Robert I and then David II cemented their authority, Edward Balliol was beavering away, shoring up his relations with England and engaging the irked ‘disinherited’ barons.

In 1332, he made a play for the throne, kicking off the Second War of Scottish Independence when he defeated David’s forces at the Battle of Dupplin Moor. He was crowned King of Scots in September of the same year.

Within just three months, however, a force loyal to David pushed Edward back across the border and he had to relinquish his briefly held crown. It wasn’t long until, buoyed by support from Edward III, he returned with English troops, which was when David and his young wife Joan fled to France in 1333.

Once again, Balliol was used as a puppet by Edward III and Scotland became virtually a vassal state again.

While David was held captive in England (following an unsuccessful attempt to return), battles raged between his supporters, including regent Robert Stewart, and those loyal to Edward Balliol. However, Edward’s power was decreasing and by 1355, he only really held sway in parts of Galloway.

In 1356, Edward Balliol finally surrendered his claim to Scotland’s throne and lived out the remainder of his days in Yorkshire on an English pension courtesy of Edward III. It is suggested his remains rest under a Post Office in Doncaster.

The battle between the Balliols and the Bruces died along with Edward Balliol in 1364. The final years of David II’s reign, however, were punctuated with attempted power grabs by his nephew, Robert Stewart, who eventually took the throne in 1371 as Robert II.

Our series on the early Kings of Scotland will continue in the next issue of Scotland. Get your copy of November/December issue, here.

Read more:

SCOTLAND MAGAZINE

Published six times a year, every issue of Scotland showcases its stunning landscapes and natural beauty, and delves deep into Scottish history. From mysterious clans and famous Scots (both past and present), to the hidden histories of the country’s greatest castles and houses, Scotland‘s pages brim with the soul and secrets of the country.

Scotland magazine captures the spirit of this wild and wonderful nation, explores its history and heritage and recommends great places to visit, so you feel at home here, wherever you are in the world.