We explore the lead up to and the repercussions of the notable Battle of Stirling Bridge in which the Scottish, led by William Wallace and Andrew Moray, outwitted the English army

MORE FROM SCOTLAND MAGAZINE

The first War of Scottish Independence kicked off in 1296 in response to King Edward I of England’s imposition of overlord status.

When Edward’s favoured ‘puppet’ King John Balliol refused to back his military action against the French, the furious English king set forth with his army in March 1296 to sack the then Scottish border town and important trading port of Berwick-upon-Tweed, leaving thousands dead.

When Balliol subsequently renounced his homage to the English king, Edward’s army followed this up with victory over the Scots at the Battle of Dunbar, effectively ending the war of 1296. Balliol promptly abdicated and was taken to the Tower of London before being exiled to France where he spent the rest of his life at the family estate in Picardy.

The English king was determined to bring to heel Scotland’s 1,800 nobles of the ruling class, but by the following year, the country had erupted in civil war.

It has long been my wish to help revive the name and reputation of Andreas de Moravia (Andrew of Moray) or, as contemporary historians have started to call him, Andy Murray. No, not the tennis player but the Norman Scot who, with William Wallace defeated the combined English forces of the Anglo-Norman John de Warenne, Earl of Surrey and Hugh de Cressingham on the River Forth at Stirling.

Alas, de Moravia was mortally wounded in the fighting and later died at the age of 40. Had he lived on, he might easily have become as celebrated in modern literature and film as his compatriot, Wallace, and, indeed, Robert the Bruce. A baron’s son, he trained for a knighthood and was a skilled leader. Sadly, events overtook his reputation. Unlike Wallace, no monument to him exists, though in recent years there have been calls for one.

Andrew had been captured some months earlier at the Battle of Dunbar and taken to Chester Castle on the English and Welsh border, from where he managed to escape over the winter months. Unfortunately, no record exists to explain how he did so but on returning to his family stronghold on the Moray Firth, he launched a guerilla campaign that swept through the entire neighbourhood. A brilliant tactician, he called upon the support of his countrymen on his extensive family estates and must have possessed sufficient charisma for them to rally to his side. He first attacked, but failed, to take Urquhart Castle on the shores of Loch Ness, moving on to seize all the other English-held fortifications in the region. English ships moored in Aberdeen Harbour were burned in a night attack.

Meanwhile, in the south-west of Scotland, William Wallace of Elderslie, the son of minor Scottish nobility, had risen up and assassinated the English High Sheriff of Lanark. North and south, de Moravia and Wallace soon joined forces at the Siege of Dundee.

Until now, Edward of England had considered the Scottish rebels little more than a nuisance and of no great consequence to be eviscerated, but on 11 September 1297, he discovered he would have to think again.

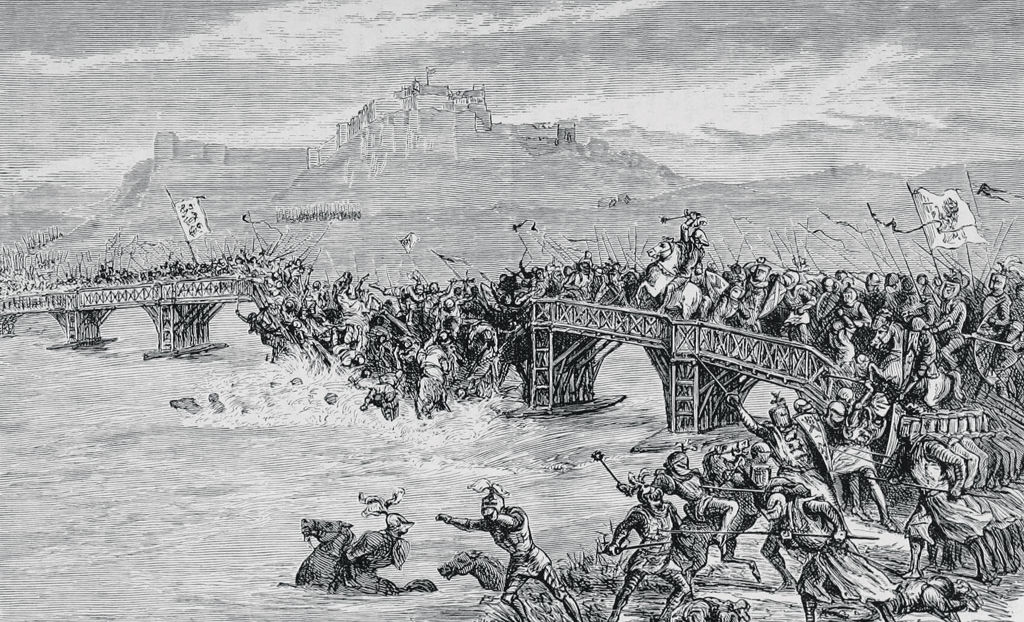

The town of Stirling, with its formidable castle, was considered to be the gateway to the north of Scotland and Edward sent his favoured generals John de Warenne, 6th Earl of Surrey, and Hugh de Cressingham to secure the region. Surrey arrived first and decided to set up camp next to the narrow wooden bridge that spanned the River Forth at Stirling, a hundred or more yards upstream from the current 15th-century bridge.

Early on that September morning, he gave order for his troops to begin crossing the river only to recall them because he had overslept.

This gives some indication of how insignificant Surrey considered the rebel forces, but he was foolish to underestimate them, for by then the Scots had taken up a strategic position on Abbey Craig overlooking flat ground to the north. The English and Welsh army, with, it should be noted, a small contingent of Scottish supporters in their number, began to cross the bridge, but arriving on the low ground they were rapidly decimated by the Scottish infantry who charged at them carrying spears.

Meanwhile, the Earl of Surrey, still on the south bank of the river, lost his nerve, ordered the bridge to be destroyed, and retreated in haste. Insult was added to injury when the English supply train was attacked by a further troop of Scots with many of the fugitive English soldiers being put to the sword.

In the aftermath, the contemporary chronicler Walter of Guisborough recorded that 100 cavalry and 5,000 English foot soldiers were killed. Hugh de Cressingham was cut down and according to the Lanercost Records, the skin from his foot was later used to create a wrap-around for the hilt of William Wallace’s broadsword.

It was a vastly traumatic defeat for the English, primarily as it proved that under certain conditions, foot soldiers could be infinitely more successful than the armoured cavalry of England. For the time being it stalled Edward’s advance into Scotland but it made the ‘Hammer of the Scots’ more determined to have his way.

Despite it being a resounding triumph, the Scottish celebrations surrounding the victorious Battle of Stirling Bridge were short-lived. There was little consolation to be gained, since although Andrew Moray survived the battle, he had been mortally wounded and soon disappeared into the annals of history. At least he was spared the grisly fate of his side-kick eight years later.

William Wallace, who was shortly afterwards knighted by the nobles of Scotland, emerged as the appointed Guardian of Scotland and, when captured in 1305, was taken to London and brutally ripped to pieces on the orders of the unforgiving King Edward. Meanwhile, where was 22-year-old Robert the Bruce while all of this was going on?

One of the three senior claimants to the Scottish throne, he had spent time at the Anglo-Norman court, and remained hitherto ambivalent about whether or not to support his distant English relative, King Edward. Besides, the Bruces were substantial landowners in England.

Robert was cautiously weighing up his options. However, when Sir William Wallace was betrayed and captured, and so brutally executed in London by Edward, Bruce rose to the occasion.

The Battle of Stirling Bridge was therefore the forerunner to Bruce’s great victory at the Battle of Bannockburn, in which he would go on to earn his place as monarch of an independent Scotland.

MORE FROM SCOTLAND MAGAZINE

SCOTLAND MAGAZINE

Published six times a year, every issue of Scotland showcases its stunning landscapes and natural beauty, and delves deep into Scottish history. From mysterious clans and famous Scots (both past and present), to the hidden histories of the country’s greatest castles and houses, Scotland‘s pages brim with the soul and secrets of the country.

Scotland magazine captures the spirit of this wild and wonderful nation, explores its history and heritage and recommends great places to visit, so you feel at home here, wherever you are in the world.