MORE FROM SCOTLAND MAGAZINE

Mary, Queen of Scots: Queen of hearts

Spending a large portion of her life in France, rightly or wrongly Mary, Queen of Scots is our most romanticised monarch

Words by Kirsten Henton

Mary, Queen of Scots’ colourful life was, as biographer Lady Antonia Fraser wrote, a tale of “murder, sex, scandal and imprisonment”, with more drama than you could shake a well-written script at.

She’s often seen as a victim of circumstance, a tragic figure vilified for her sexuality and suggested involvement in devious plots.

Yet, this overly simplistic view undermines the authority she wielded. This imposing (she was 5ft 11in – a little over 1.8 metres) and, according to Fraser, strikingly attractive queen, had presence, personality, and power. Elegantly portrayed in continental clothes and draped in jewels, she was the first woman to rule Scotland in her own right. She succeeded, for a time, as the Catholic monarch of a Protestant kingdom.

She led troops into battle, briefly wore the French crown and remained gracious even as her neck prostrated the block. Here we look at her story in miniature to see the real legacy she left behind.

Who was Mary, Queen of Scots?

Mary Stewart came to the throne at just six days old following the death of her father, King James V of Scotland in 1542. Crowned on 9 September 1543 at Stirling Castle, Mary ascended as yet another Stewart minor, leaving Scotland open to the wants of the ambitious.

Even by the standards of the time, this was a lively period of significant change. From Renaissance influences to England’s Reformation (Henry VIII’s 1534 break from the Catholic church) that upended society south of the border while spurring Scotland’s own Reformation north of it.

In a bid to safeguard Mary from the period known as the Rough Wooing, an eight-year English campaign designed to both weaken the Scottish state and break the Auld Alliance with France, she was whisked to the French court in 1548 and Scotland was ruled by a regent. In 1558, aged 15, she married the Dauphin of France. He became King Francis II (therefore King of Scotland; Mary, Queen of France) in 1559, but he died the following year.

Meanwhile, the Reformation crisis mushroomed as the likes of John Knox officially transformed Scotland into a Protestant nation in 1560. Changes were afoot in England too as Elizabeth I began her monumental reign in 1558.

It was in this febrile environment that Mary returned to her homeland as a virtual stranger aged just 19 in 1561.

A widow, a devout Catholic and a queen, Mary began her rule on a tinderbox of religious and political tensions. However, she showed remarkable tolerance, allowing the status quo to continue. Even with John Knox preaching wildly against her, Mary navigated her way between the two sides. She kept many of the Reformation lords on as advisors, including her illegitimate half-brother, James Stewart, Earl of Moray.

As Dr Anna Groundwater, acting keeper of Scottish history & archaeology at National Museums Scotland puts it: “Despite the difficulties, Mary was relatively successful in the first years of her personal reign.”

She continues, “Mary had been brought up to be queen and had an innate confidence in her monarchical power, which helped her to re-establish the authority of the Stewart monarchy in Scotland. She demonstrated that she could exert authority, take decisions, lead her supporters into battle and suppress rebellion.”

Who did Mary, Queen of Scots marry?

Mary endured great heartache precipitated by her questionable romantic instincts. As Groundwater puts it, “Mary’s power was undermined partly by her unfortunate choice in men” and, as John Guy writes in his book, Queen of Scots: The True Life of Mary Stuart, “She ruled from the heart and not the head.”

A big shift came with her marriage to her Catholic half-cousin, Henry, Lord Darnley in 1565 without the consent of parliament. Darnley was, as Groundwater states, “a weak and vindictive wastrel” and the marriage antagonised everyone. Moray and the Protestant lords disliked Darnley, while in England, Elizabeth felt threatened as their union only strengthened claims on the English throne, especially after the birth of their son, James (the would-be James VI and I).

Darnley, arrogant and power-hungry, sought to usurp his wife and became a useful if unwitting agent for Mary’s enemies, overseeing the murder of her Catholic Italian advisor – some say lover – David Rizzio, who was brutally stabbed in front of the pregnant queen.

The marriage broke down and, after flip-flopping between supporting and opposing Mary, Darnley was found murdered in February 1567. Mary and – enter stage left – James Hepburn, Earl of Bothwell, were suspected of involvement in his death.

The now-notorious Bothwell was hastily tried and acquitted before it’s said he kidnapped, raped, and forced Mary into marriage in May 1567. Another unpopular pairing, the Catholics didn’t recognise Bothwell’s divorce from his previous wife, which had taken place just 12 days earlier. Those on both sides of the aisle were also dismayed that Mary would marry the man assumed to have murdered her second husband Darnley, his abuse taking a notable backseat.

Groundwater says his “arrogance was to antagonise the nobles and lairds on whose support Mary depended.”

Why was Mary Queen of Scots imprisoned?

The murder of Darnley, her marriage to Bothwell and the bubbling distrust between Catholic and Protestant factions combined to undermine Mary’s authority. This came to a head in June 1567 at the Battle of Carberry Hill, which was more of a rebellious stand-off between Mary and Bothwell’s dwindling army of supporters and the troops of the Protestant lords that eventually fizzled out.

Pregnant Mary was imprisoned in Loch Leven Castle, where she miscarried twins, and on 24 July 1567 was forced to abdicate in favour of her son, one-year-old James, with Moray as regent. Mary escaped in May 1568, briefly raising a force that was defeated by Moray at the Battle of Langside before fleeing south, leaving Scotland for the last time.

Elizabeth I was a decade into her reign when her cousin, Mary, stepped ashore in England after fleeing across the Solway Firth seeking help. Elizabeth, all too aware of Mary’s claim to the English throne and her appeal to England’s marginalised Catholics, was in a quandary. What to do with this legitimate threat, one whom she’d never met but was, in Mary’s own words, “of one blood, of one country, and in one island”?

Mary was taken into protective custody, where she remained for the next 19 years, moving from one residence to another, including Bolton Castle and Chatsworth House. Although treated well with ample comforts, Dr Susan Doran writes, Mary felt perpetual “anguish and anxiety” at her situation. She relentlessly campaigned for her release, pleading with Elizabeth through letters and scheming with her supporters, even appealing to her son James VI, although he had aligned himself with Elizabeth.

Why was Mary Queen of Scots executed?

Detained, Mary remained a danger to Elizabeth. She was a galvanising force for Catholic plotters attracting support from far and wide, including the Pope. Ultimately, Mary’s bids for freedom through coded letters led to her demise with the infamous Babington Plot.

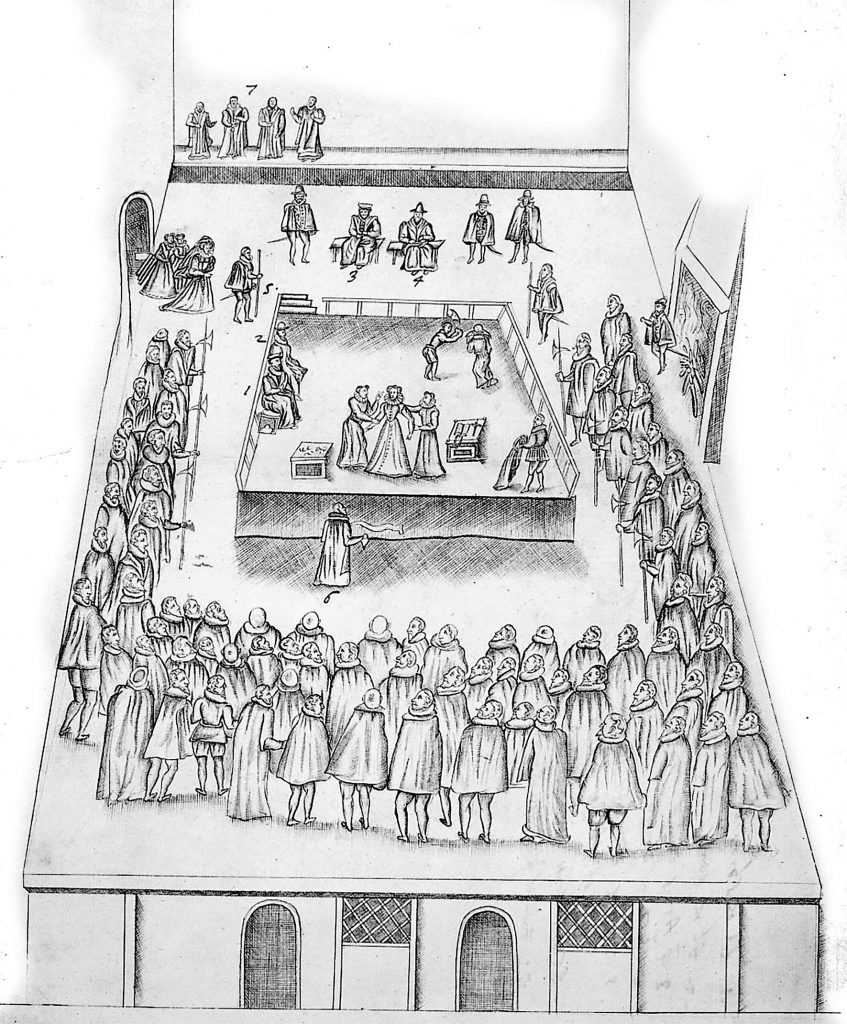

This series of contrived correspondences, the authenticity of which remains a source of great debate, plotting the death of Elizabeth I was used as evidence to try and convict Mary of treason. She was somewhat gruesomely executed on 8 February 1587, aged 44.

Venture into Westminster Abbey and you’ll find an elaborate marble arch over the tomb of Mary, Queen of Scots. It’s impossible not to feel a sense of pity for a woman so capable and, as Groundwater says, with such “style and magnetism.”

This is in part, she continues, because “our judgement of Mary is often shaped by the knowledge of her tragic ending.” But let’s not forget, she was a strong, courageous woman and we should “remember her as she was for some time: the magnificent Queen of Scots.”

During her imprisonment, Mary aptly embroidered the words “In my end is my beginning.” That she is still so fervently discussed, written, and talked about, enacted on stage and in film, is perhaps her greatest legacy of all.

Our series on Scotland’s kings and queens comes to its conclusion with Mary’s son, King James VI, next issue.

Read more:

SCOTLAND MAGAZINE

Published six times a year, every issue of Scotland showcases its stunning landscapes and natural beauty, and delves deep into Scottish history. From mysterious clans and famous Scots (both past and present), to the hidden histories of the country’s greatest castles and houses, Scotland‘s pages brim with the soul and secrets of the country.

Scotland magazine captures the spirit of this wild and wonderful nation, explores its history and heritage and recommends great places to visit, so you feel at home here, wherever you are in the world.