The story of how Mary, Queen of Scots escaped the clutches of Henry VIII and how her formative years in France shaped her

MORE FROM SCOTLAND MAGAZINE

Words by James Irvine Robertson

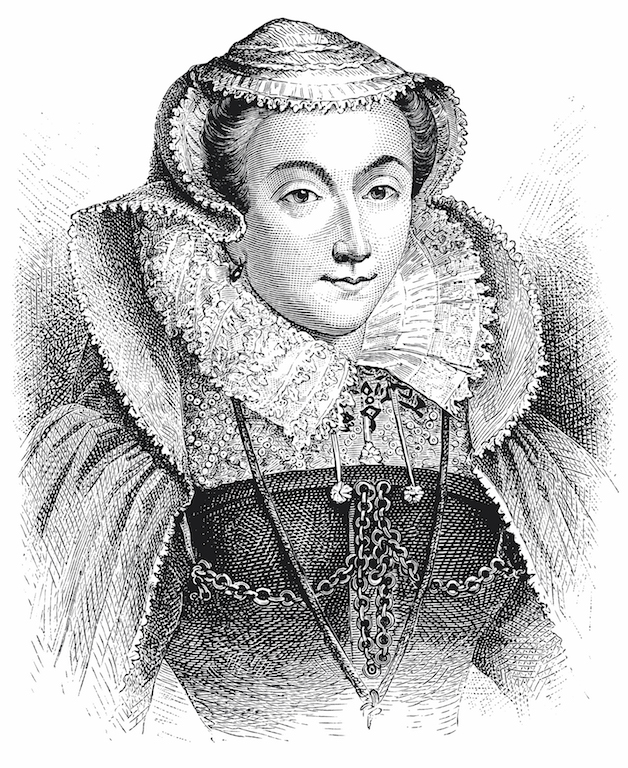

In the mid-16th century, the Reformation tore peoples and nations apart. Trapped in the turmoil all her life was Mary Stuart, who became known as Mary Queen of Scots.

Born in 1542, Mary was just six days old when she succeeded to the throne of Scotland. Her father, King James V, died shortly after his troops were humiliated at the Battle of Solway Moss, countering an army launched across the border by Henry VIII to try to force the Scottish king to support the Protestant faith. James had already seen the death of two young sons and the newborn child, Mary, represented the future of his dynasty.

Henry was well aware of it. Within six months he floated a treaty proposing that Mary should marry his five-year-old heir, the future Edward VI, and thus unite the two nations. Under Henry’s plans, he would take charge of the infant until the marriage.

But, although the Regent and the Protestant faction supported the English match, Mary’s French mother, Mary of Guise, and her subtle Cardinal, David Beaton, were against it. They preferred a French union that would betroth the child to the Dauphin, the heir to France’s King Henry II.

In 1543, following Henry’s arrest of Scots merchant ships heading for France, opinion moved towards a French alliance. The Regent, Arran, switched sides from Protestant to Catholic and Mary was crowned in Stirling.

Henry was incandescent and sent an army, pillaging and burning, into Scotland – this was the beginning of what became known as the ‘Rough Wooing’. The Battle of Pinkie Cleuch, just east of Edinburgh, in 1547 was a devastating defeat for the Scots and the then five-year-old Queen was moved to Dumbarton Castle for safety. The French promised arms and men and the Regent agreed to the marriage.

No other child in Europe enjoyed so cosseted and luxurious a childhood as Mary did in France. The extravagant French court travelled between magnificent chateaux. She and the four-year-old dauphin instantly took to each other. The king, Henry II of France, described her as the most perfect child he had ever seen. He asked that she and his eldest daughter Elizabeth should share a bedroom so that they would become friends. As a crowned queen and future queen of France, Mary was given precedence over his own little princesses. Her clothes were even more sumptuous.

Women dominated the French court. Queen Catherine de Medici supervised the royal nursery in which Mary was embedded. Her own attendants, including her four Marys, were sidelined. Mary’s grandmother, Antoinette, was matriarch of the immensely powerful de Guise family. Her son, the Duke of Guise became a hero in 1558 when he captured Calais, the last English possession in France.

Mary learned to play the lute and virginals. She was proficient at prose, poetry, falconry, horsemanship and needlework. She learned French, Italian, Greek, Latin and Spanish. She was taught to draw, dance and sing. The nursery had a total of 22 lapdogs as well as cage birds, falcons and horses attached to it.

The dauphin was sickly but developed an all-consuming passion for hunting. Choirs performed for the children; troupes of actors, jugglers and tumblers entertained them; armies of attendants – including nursemaids, cooks, doctors, tutors, priests and valets – looked after them.

However, ominous clouds were gathering in France. Financing wars had left the Crown deep in debt. The conflict between Catholics and Protestants that would lead to three million dead in the country was getting under way, but Mary and the royal children were protected from all of this.

Mary was universally loved. She was spirited, bright, beautiful, tall, devout and had a sunny disposition. She became thoroughly French. She spelled her name Stuart rather than Stewart as the French language had no ‘w’.

In April 1558, when she was 15, she married the dauphin, Francis, in a lavish ceremony in Notre Dame in Paris. In November that year her cousin Elizabeth succeeded to the throne of England.

In the eyes of most Catholics, Elizabeth was illegitimate. It was Mary, through her grandmother, Margaret Tudor, who was the rightful Queen of England. Her arms quartered the royal arms of England with those of France and Scotland, ratcheting up the threat the oblivious Mary represented to Elizabeth.

In July 1559 King Henry II died after a jousting accident and Francis and Mary were crowned King and Queen of France. The new king was not up to the role. He was both physically and mentally immature. The couple happily shared a bed, but he was incapable of consummating the marriage. He spent almost all his time hunting rather than showing interest in matters of state.

The country, therefore, was run by Mary’s two Guise uncles and the dowager queen Catherine. Mary began to learn statecraft through accompanying and sitting beside her at council meetings.

Mary of Guise had been Scottish Regent since 1554 with the impossible task of balancing Protestant and Catholic factions. She had spent a year in France (1550-1) during which she and her daughter developed a loving relationship that endured through frequent letters. She died in June 1560 and the young Mary was prostrated with grief. Her husband died six months later and once again she was grief-stricken.

The new king of France was Francis’s brother, Charles, who was 10. Catherine lost interest in her daughter-in-law and concentrated her energies on promoting her son and her family. She ousted Mary’s de Guise relations and became Regent of France.

So, what was Mary to do? She could have spent a luxurious life in France. She was Duchess of Touraine with rich estates to support her, but she was now making her own decisions.

A marriage to the heir of the Spanish throne was a possibility, but Catherine scotched that. In her native country, John Knox had helped nurse through the Protestant Revolution. Mary was hardly relevant – unknown, French, Catholic, young, and as much a virgin as Elizabeth. But Mary was never one to shirk a challenge. She was Queen of Scotland, after all.

Ignoring the fact that Queen Elizabeth would not grant her safe passage, on 14th August 1561, Mary set sail for Leith and went forth to claim her birthright.

Read more:

MORE FROM SCOTLAND MAGAZINE

SCOTLAND MAGAZINE

Published six times a year, every issue of Scotland showcases its stunning landscapes and natural beauty, and delves deep into Scottish history. From mysterious clans and famous Scots (both past and present), to the hidden histories of the country’s greatest castles and houses, Scotland‘s pages brim with the soul and secrets of the country.

Scotland magazine captures the spirit of this wild and wonderful nation, explores its history and heritage and recommends great places to visit, so you feel at home here, wherever you are in the world.