A century after his legendary Olympic Games win, we look back at the life and incredible legacy of Eric Liddell

MORE FROM SCOTLAND MAGAZINE

Sprinting to victory at the Paris Olympics 100 years ago on 11 July 1924, the same year a locomotive numbered ‘4472’ took on the name Flying Scotsman, Eric Liddell was one of Scotland’s finest.

An Olympic champion, international rugby player, and a Christian missionary who was immortalised in the 1981 Oscar-winning film Chariots of Fire, it seemed there was little Eric Liddell couldn’t achieve if he put his mind to it.

Born in China to Scottish parents, James Dunlop Liddell and Mary née Reddin, Eric was sent to the UK to boarding school in south London from the age of six (1908-20) but he also enjoyed family life in the Scottish capital whenever his parents returned to the UK.

Edinburgh was a city that became a true home to Eric Liddell, as he studied Pure Science at the University of Edinburgh, and it was while studying that his athletic prowess came to the fore, his feats on the track reported by the press amid talk of a future Olympic career. He was that good.

Chosen to speak for Glasgow Students’ Evangelistic Union, the other characteristic that was already self-evident about Liddell was his devout Christianity.

Liddell practised and preached at Edinburgh’s Morningside United Church at Holy Corner. The church outgrew its premises and eventually relocated across the road to what is today the Eric Liddell Community centre. Today Eric Liddell is remembered in a stained-glass window that depicts him in his trademark running style. By the time Liddell packed his running spikes to travel with the GB team to the Paris Games, he was already a Scottish rugby international. Having turned out for the Edinburgh University side, he then played for Edinburgh District (1921-22), appearing in inter-city matches against Glasgow District, before being capped seven times for the full Scottish side in the 1922 and 1923 Five Nations, scoring four tries.

In 1923 Eric Liddell also won the 100-yard sprint at the AAA Championships, setting a British record of 9.7 seconds in the process, and achieving national recognition for the first time.

One famed episode in his athletics career came in July 1923 when Liddell fell early in a 440-yard race when competing for Scotland against England and Ireland, before dragging himself up and recovering a 20-yard deficit to breast the tape first. Although this happened in Stoke-on-Trent, artistic licence saw Chariots of Fire move the action to the playing fields of George Heriot’s School, Edinburgh.

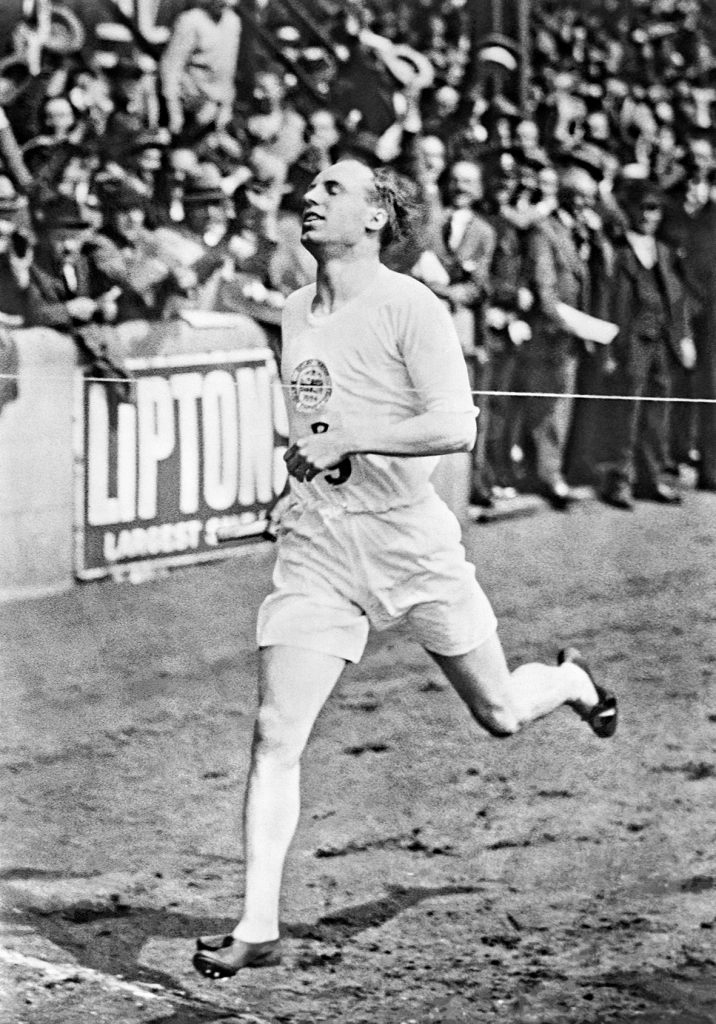

Liddell’s running style was accurately depicted though; with head thrown back, mouth wide open, and arms flailing like a distorted windmill. It was a gait that had him dubbed ‘the ugliest runner who ever won an Olympic championship’.

The 1924 Paris Olympics saw Liddell become a double medallist as not only did he win Gold in the 400 metres, but also Bronze in the 200 metres.

A man of conviction and Christian commitment, Liddell withdrew from his favoured 100 metres when it became apparent the heats were to be held on a Sunday. He also refused to participate in the relays for the same reason. Instead, he tackled the 400 metres, a quite different race – a cross between sprint and distance – and won it. At the heats stage, the fancied Americans laughed at Liddell’s awkward running style; once the final was run, no one was laughing.

After the halcyon days of the Olympics, Liddell graduated with a B.Sc. from Edinburgh in 1924. A plaque at the university (St George Square) recalls his achievements and residence there from 1922-24.

Liddell’s final races on British soil came in the Scottish AAA meeting at Hampden Park, Glasgow, in 1925. He won the 100-yards, 220-yards and 440-yards, and he was also a member of a successful relay squad.

Liddell returned to China in 1925 to work as a missionary teacher. Although he was able to return to Scotland twice: in 1932, when he was ordained a minister of the Congregational Union of Scotland; and in 1939, China was his base for the remaining two decades of his life.

Whilst he still competed in occasional athletics meets, Liddell chose his work over his sport. Asked about their relative merits, he expressed little regret over eschewing the track; his mission was more important.

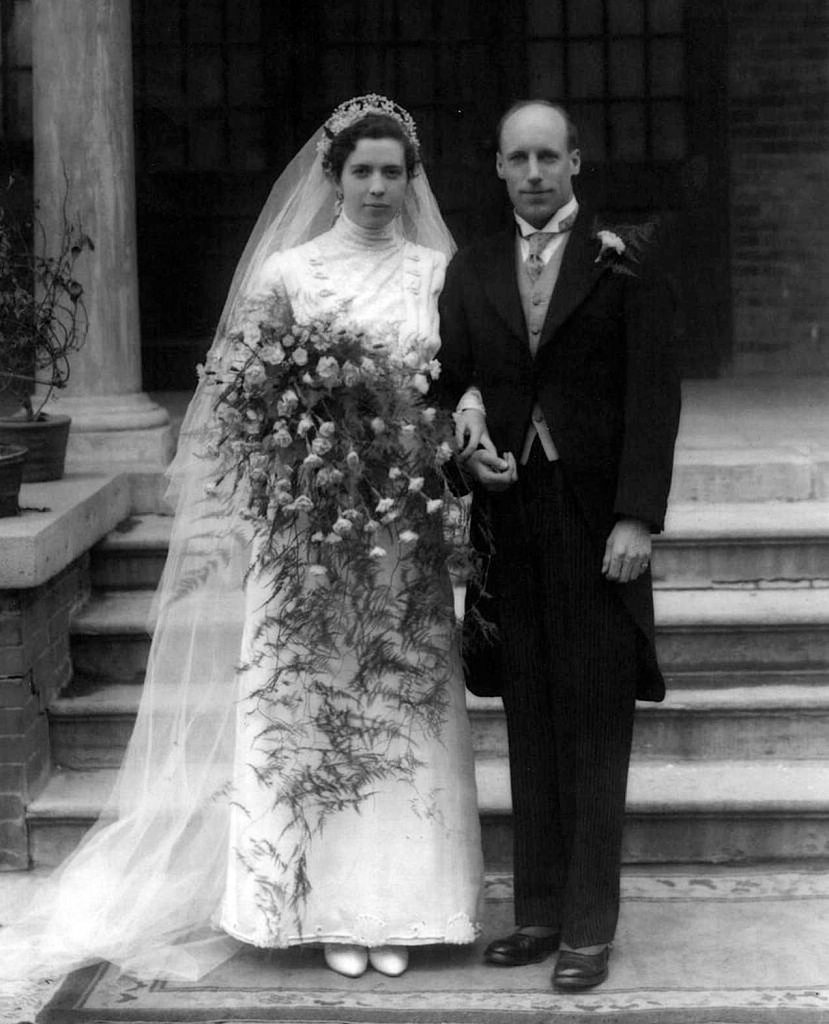

In 1934 Eric married Florence Mackenzie, a Canadian also of missionary parentage, and the couple had three daughters.

However, the China station proved perilous, certainly from July 1937, the most commonly accepted date for the start of the Sino-Japanese War, which preceded the Second World War and continued right through to that war’s conclusion in 1945, with Liddell hazardously crossing Japanese army lines.

By 1941, the situation in China had become so dangerous that UK nationals were advised to return home. Florence, pregnant with Maureen, the couple’s youngest daughter, left for the sanctuary of Canada; Eric Liddell fatefully stayed put, too disinclined to abandon those he was helping.

The Japanese moved into the area where Liddell was working in 1943, took over his mission station, and held him in the Weihsien Internment Camp, which had been set up for civilians.

Eric Liddell died on 21 February 1945 in the internment camp; it’s believed he had been suffering from a brain tumour. He died aged 43, just five months before the camp was liberated; sadly he didn’t live long enough to meet his youngest daughter.

Memorial services were held that year in both Edinburgh and Glasgow and the Eric Liddell Centre (now Community) was established in Edinburgh in 1980 to honour his dedication to community service.

In Chariots of Fire, Liddell was portrayed by fellow-Scot and University of Edinburgh graduate, Ian Charleson, who also died young – aged 40.

In January 2022, on the centenary of his first cap, Liddell was inducted into the Scottish Rugby Hall of Fame, while the Eric Liddell Gym was opened at the University of Edinburgh in 2023. This Flying Scotsman certainly won’t be forgotten anytime soon.

This is an extract. Read the full article in the May/June 2024 issue. Available to buy from Friday 12 April here.

Read more:

MORE FROM SCOTLAND MAGAZINE

SCOTLAND MAGAZINE

Published six times a year, every issue of Scotland showcases its stunning landscapes and natural beauty, and delves deep into Scottish history. From mysterious clans and famous Scots (both past and present), to the hidden histories of the country’s greatest castles and houses, Scotland‘s pages brim with the soul and secrets of the country.

Scotland magazine captures the spirit of this wild and wonderful nation, explores its history and heritage and recommends great places to visit, so you feel at home here, wherever you are in the world.