We investigate the origins of Alba – the first Kingdom of Scotland

MORE FROM SCOTLAND MAGAZINE

Scotland is skilled in the art of telling a good old tale of yore. But in the case of early medieval Scottish history, the difficulty lies in stripping away the myths surrounding folklore to get to the truth of how Scotland as we know it today began to take shape. And it’s no easy task: it’s a seriously complex period with a comparative lack of sources that experts dedicate entire careers to comprehending. Here, we’re joining the story in the 9th century, looking at the events that led to the emergence of the modern nation of Scotland.

The early medieval age – roughly 5th to 10th centuries AD – can’t help but sound foreboding. The Romans had long gone and the Vikings were settling into their raids. It was a time of great social and political adjustment, the land a patchwork of tribes and ancient cultures that had seen the benefit of strength in numbers, combining their interests to forge stronger kingdoms. Within the pages of The New Penguin History of Scotland, it’s said that “Scotland’s early medieval past boasts perhaps the most diverse collection of peoples and languages to be contained within any emerging medieval nation-state.” As such, it concludes that “there is no ‘original Scot’ who will sit comfortably on the page without a mess of caveats.” Therefore, in order to try and comprehend how Scotland looked and behaved in the 9th century, we need to banish any notion of Scotland as one country with a single identity at this time.

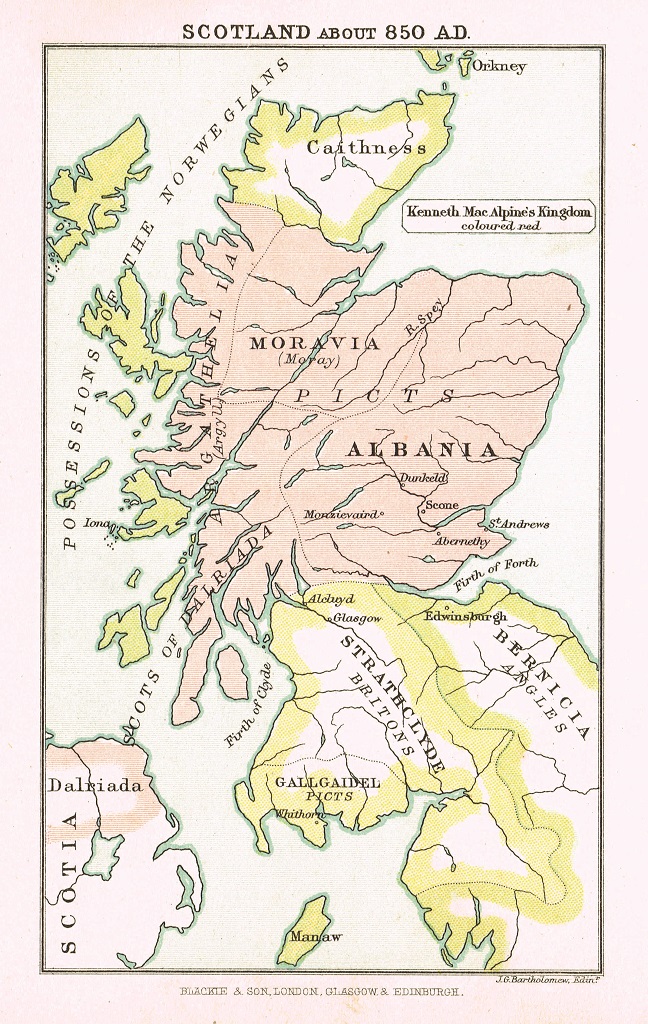

The main players in this particular chapter are the Picts and the Scots, however they weren’t alone. Many tribes had come together under various kingdoms over the preceding centuries, including the Anglican kingdom of Northumbria and the Britons who, between them, occupied land from the south up to the Forth-Clyde isthmus. In the west, the Gaelic-speaking kingdom of Dál Riata had dominated the land of Argyll and northeastern Ireland from the 5th century AD. The Gaels, or Celtic people who inhabited these lands, were known as Scots – a term to be used with caution.

As Dr Adrián Maldonado, Glenmorangie Research Fellow at National Museums Scotland, points out, “‘Scot’ is historically correct to discuss the people of Dál Riata, [but] it is easily conflated with later ‘Scotland’ and modern ‘Scots’.” By the 9th century, the power and influence of Dál Riata were in decline. To the north and east lay Pictland which, broadly speaking, scooped up areas from Fife northwards through Easter Ross into Sutherland, Caithness and possibly the northern isles. When it comes to the Picts – long thought of as wild, painted pagans – the one thing that’s clear is that, well, nothing’s clear. Or, at least, few things can be said with absolute certainty. “The Picts did have texts, histories and genealogies at one point,” confirms Maldonado, “but for various historical reasons they did not survive.” Some exceptional stone carvings, such as the Sueno’s Stone in Forres, Shandwick Stone in Easter Ross and the Hilton of Cadboll Stone in the National Museum of Scotland, Edinburgh, as well as metal work survive, but a detailed translation of the symbols contained within remains elusive.

Other scant evidence exists in place names, monument inscriptions and within the texts of other languages, plus later works from sources like the English Benedictine monk Bede, although these are treated with a questioning eye. Just like the Scots, by the 9th century, the Picts were seeing the destabilisation of their kingdom.

It’s into this dynamic that one of Scottish history’s most revered characters steps forward. Legend will tell you that Kenneth MacAlpin, or Cináed mac Ailpín, rose up from within the Scots of Dál Riata to push eastwards, gaining control of large swathes of land, thereby bringing an end to the Pictish way of life and establishing the first Kingdom of Scotland. However romantic, this tale holds little credibility today.

Crumbs of information exist that help to form a picture of who MacAlpin was. It’s suggested that far from being “a sort of Dál Riata sleeper agent who succeeded in infiltrating the doomed Pictish kingdom,” as Maldonado puts it, he was of Pictish ancestry as he’s referred to as ‘King of the Picts’ in contemporary sources. Although, Maldonado highlights that “very little can be said for certain” about his origins.

It’s generally accepted that between 839 AD and 848 AD (843 AD is frequently proffered), MacAlpin became King of the Picts and Scots in what would become known as the Kingdom of Alba. While there’s no denying that the MacAlpin dynasty ruled this unified kingdom, questions remain over not only who he was, but how the kingdom came into being.

“The Scots never ‘gained control’,” states Maldonado, “this may be one of the biggest myths of medieval Scottish history.” In fact, the reality may have been far more pragmatic. The relentless push of Christianity, and its associated Gaelic language, eastwards and the increase of ferocious Viking raids from the west played their part in reshaping the landscape and causing economic difficulties that made the Scots in the west look for security elsewhere.

The perceived domination of the Scots over the Picts could be viewed instead as a cohesive assimilation in which the more international Gaelic language, ever-increasing power of the Christian church and intermarriage led to the Picts’ culture being overridden. Of course, as Tim Clarkson writes in his book The Makers of Scotland, the Picts didn’t biologically disappear, they “simply lost the political and cultural identities that had formerly defined them as separate peoples.” Although, perhaps the Picts left a different kind of legacy. The New Penguin History of Scotland asserts that “the power, prosperity and machinery of the Pictish kingdom laid the foundation for the Scottish one that would take its place.” It’s a less flamboyant, more practical version of events that warrants consideration even though it challenges one of the greatest legends of early medieval Scottish history.

However this unification occurred, it’s accepted that the Kingdom of Alba emerged in the 10th century ruled by the MacAlpin dynasty until the mid-11th century. Crucially, “Alba was the name of a land, not a single people,” states Maldonado. The stickiest issue here is the terminology. It’s not entirely clear when the term ‘Kingdom of Alba’ became part of the vernacular or when it was superseded by ‘kingdom of Scotland’. “Cináed [MacAlpin] only became seen as the ancestor of the kings of Scots once the term ‘Scotland’ began to take shape,” Maldonado explains, “which was seemingly in the 11th to 12th centuries.”

This suggests it happened later, written into the annals retrospectively, while others put forward the idea that it was an Anglo-Saxon word used by the English to describe the people of Dál Riata and later Alba that can be traced back as early as 600 AD. What we can say is that the Kingdom of Alba, with its influences from both the Picts and the Scots, lay the foundations of what would become the first recognised Kingdom of Scotland. It unified the land in a way that had not been seen before and germinated the idea of the modern Scotland we know and love today.

If you’re interested in finding out more, visit the Early People gallery at the National Museum of Scotland, in Edinburgh. For clues to Scotland’s Pictish past, both the Meigle Sculptured Stone Museum with 26 Pictish stones, in Perthshire, and St Vigeans Sculptured Stones Museum (by appointment only) with 38 Pictish stones, near Arbroath in Angus (both looked after by Historic Environment Scotland) are unmissable. You’ll find Pictish ruins at Burghead Fort in Moray with its mysterious rock-cut well, plus a monastery and artefacts at Tarbat, near Portmahomack. nms.ac.uk; historicenvironment.scot; burghead.com; tarbat-discovery.co.uk

Read more:

MORE FROM SCOTLAND MAGAZINE

SCOTLAND MAGAZINE

Published six times a year, every issue of Scotland showcases its stunning landscapes and natural beauty, and delves deep into Scottish history. From mysterious clans and famous Scots (both past and present), to the hidden histories of the country’s greatest castles and houses, Scotland‘s pages brim with the soul and secrets of the country.

Scotland magazine captures the spirit of this wild and wonderful nation, explores its history and heritage and recommends great places to visit, so you feel at home here, wherever you are in the world.