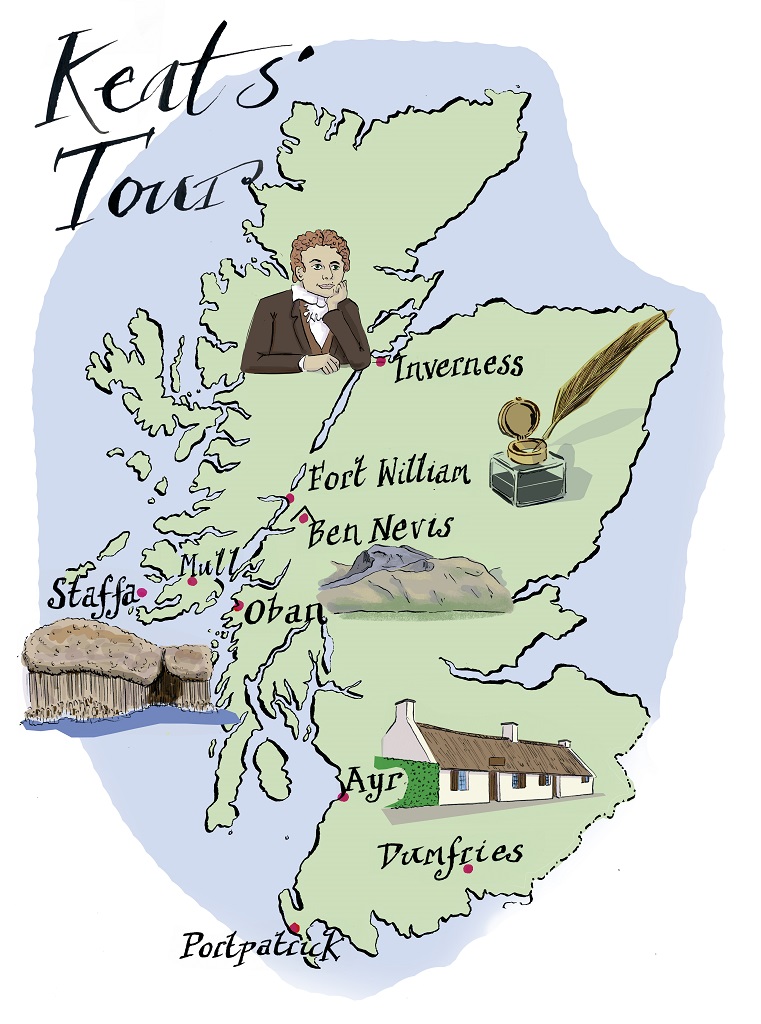

In the bicentenary year of his death, we chart the Scottish tour that proved revelatory for that most English of poets, John Keats

MORE FROM SCOTLAND MAGAZINE

Two hundred years ago this year, the poet, John Keats, died in Rome, where he had gone to convalesce after contracting tuberculosis. Aged just 25, Keats left behind an impressive collection of work, made even more remarkable by the fact that he only took the decision to concentrate on his writing three years before his death. A trip he made to Scotland in the summer of 1818 played an important part in this decision-making process.

Accompanied by his friend, Charles Armitage Brown, the poet set off from London in mid-June of that year on a walking tour of northern England and Scotland. The events surrounding the expedition are pleasingly well-documented. Keats wrote a series of detailed letters to family and friends, while his companion kept a journal.

Having taken the coach from Carlisle to Dumfries, in southwest Scotland, the pair arrived on the afternoon of 1 July 1818. They immediately went to visit Robert Burns’ grave in St Michael’s Churchyard before dinner. John Keats declared in a letter to his brother, Tom, that the tomb was “not very much to my taste, though on a scale large enough to show they wanted to honour him”.

From Dumfries the two travellers made their way west to Portpatrick, where they took the ferry to Ireland, but were back on Scottish soil within two days.

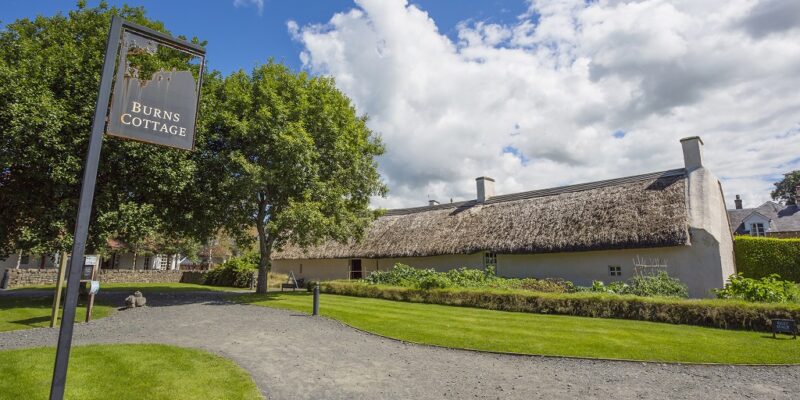

They then continued their journey northwards towards Ayr, arriving at Burns’ cottage in Alloway on 11 July. Keats had intended the visit to the birthplace of one of his literary idols to be a highlight of the tour but he was underwhelmed.

While under Burns’ roof, John Keats attempted to write a celebratory poem in honour of the occasion, but later confessed to a friend that the lines he produced were “so bad I cannot transcribe them”. The whisky that the pair drank to Burns’ memory may well have contributed to what Charles Brown later memorably described as “the annihilation of his poetic power”. However, Keats’ main issue appears to have been with the garrulous old caretaker who showed them round. He was, asserted Keats, “a mahogany faced old Jackass” who talked so much that “his gab hindered my sublimity”.

John Keats did find much to admire in the surrounding countryside, describing the approach to Ayr as “extremely fine”. He had come to Scotland intent on finding beautiful landscapes to enjoy, remarking in one letter that he had embarked on his northern adventure in the belief that “it would give me more experience, use me to more hardship, identify finer scenes, load me with grander mountains and strengthen more my reach in Poetry, than would stopping at home among books”.

The poet’s expectation of experiencing “hardship”, whilst ostensibly being on an extended holiday, may appear odd, but the truth is that this was no casual walking trip. Keats and Brown were determined to take advantage of the early daylight to be enjoyed on July mornings, often rising from their beds at 4am and walking for several hours before even stopping for breakfast.

They were not equipped with the detailed maps and guidebooks that travellers take for granted today. On the morning of 17 July this meant that their breakfast was particularly delayed. Keats records that: “We were up at 4 this morning and have walked to breakfast 15 miles through two tremendous Glens – at the end of the first there is a place called Rest And Be Thankful which we took for an inn – it was nothing but a stone and so we were cheated into 5 more miles to breakfast”.

In addition, Keats and Brown were travelling on a tight budget. On arriving in Oban on 21 July, the pair proposed to travel across the water to the Inner Hebrides. Keats was particularly keen to visit Fingal’s Cave on Staffa. However, after discovering the expense this would entail, the impoverished young men were initially compelled to abandon the idea, only to change their mind the following morning when they found a guide who offered to show them “the Curiosities” of the islands at a more reasonable cost.

This involved undertaking a gruelling trek across Mull through boggy terrain in pouring rain. They spent their first night on the island in a shepherd’s hut “into which we could scarcely get for the Smoke through a door lower than my Shoulders”, Keats recalled.

Many of the islanders they met did not speak any English, but Keats was quick to praise their kindness, remembering how on asking for directions at a cottage, “a young woman without a word threw on her cloak and walked a mile in a mizzling rain and splashy way to put us right again”.

The pair did eventually make it across Mull to Iona and Staffa, but it came at a cost to the poet’s health. On returning to Oban on 26 July, they were compelled to rest for a few days before heading on to Fort William and Inverness because Keats was suffering from a sore throat.

When they did set out on the next leg of their journey north, Keats was determined to continue with the climb up Ben Nevis, which the pair had planned. He was still far from well, but his account of the trip reveals him to have been in high spirits.

Having set off “about five in the morning with a Guide in the Tartan and Cap”, the pair eventually reached the top several hours later “after much fag and tug and a rest and a glass of whisky apiece”. With the mist swirling around him at the summit, Keats even found the energy to write a sonnet.

That climb up Ben Nevis proved to be the last great adventure of Keats’ northern tour. On arriving at Inverness, he saw a doctor who, according to Brown, found the poet “too thin and fevered to proceed on our journey”.

Keats took a coach to the port of Cromarty, from where he caught a boat back home to London, leaving Brown to continue the tour alone.

Despite its premature ending, the walking tour of Scotland did provide Keats with the experience and inspiration he had craved. In the three years that followed, he went on to write some of the most memorable poems in the English language before his premature death in Rome in February 1821.

Read more:

Herstory: The Real Mary King’s Close celebrates Women’s History Month

MORE FROM SCOTLAND MAGAZINE

SCOTLAND MAGAZINE

Published six times a year, every issue of Scotland showcases its stunning landscapes and natural beauty, and delves deep into Scottish history. From mysterious clans and famous Scots (both past and present), to the hidden histories of the country’s greatest castles and houses, Scotland‘s pages brim with the soul and secrets of the country.

Scotland magazine captures the spirit of this wild and wonderful nation, explores its history and heritage and recommends great places to visit, so you feel at home here, wherever you are in the world.