MORE FROM SCOTLAND MAGAZINE

We investigate whether Highlander James Macpherson, the man behind the Ossian Hoax, was really the fraudster he was made out to be, or just a very good storyteller

WORDS Janice Hopper

The tale of the 18th-century Ossian hoax is one of the most complex and unusual yarns of the times. It grabbed headlines, involved influential figures around the world, and was the talk of the town. A simple version of this narrative sets the scene during the height of Enlightenment Edinburgh, when a young Scot, James Macpherson, ventured to his Highland homeland in the 1760s to interview native Gaelic speakers and storytellers, to track down ancient tales that had been passed down the centuries by oral tradition or captured in ancient manuscripts.

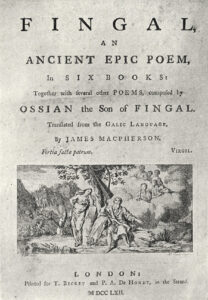

Remarkably, the young man swiftly struck gold, uncovering the poems of a 3rd-century bard called Ossian, who told the tale of Fingal, a Scottish warrior king. Such finds were declared remarkable works to rival the likes of Virgil and Homer. Macpherson’s collection of translations, Fingal, was published to great acclaim in 1762, quickly followed by Temora and The Works of Ossian.

Macpherson became a celebrity, invited to the most refined coffee houses and gatherings, from Edinburgh to London. When something seems too good to be true, it often is. Critics such as Samuel Johnson called for the written sources Macpherson claimed to have found to be shared. When these weren’t forthcoming, the Scot’s great finds were declared a sham and his celebrity status quickly shifted to that of a cause célèbre.

Centuries of investigation now suggest that the Ossian poems were most likely a combination of original material, borrowed folklore and personal embellishment, but writing off Macpherson’s poems as a ‘hoax’ is too simplistic. It’s essential to explore the background and context to this story.

Firstly, nobody becomes a sensation overnight or on their own. In the 1750s Macpherson studied at the University of Aberdeen, where classical scholar, Thomas Blackwell, opened his eyes to the fact that the ancient Highland and Gaelic culture he complacently grew up with held authentic cultural value. From the nurturing role of Blackwell, Macpherson was taken under the wing of a more ambitious and hugely respected figure in the literary world, Hugh Blair of the University of Edinburgh, and Britain’s first dedicated chair of English Literature.

Blair financed Macpherson, arranged for the publication of the Ossian poems, and wrote a preface to Macpherson’s Fragments of Ancient Poetry, published in 1760. Blair didn’t ask to be misled or actively orchestrate a ‘hoax’, but he, and the Scottish literary establishment, had an appetite for Scotland to shine, following the 1707 Act of Union and the decimation of Jacobite forces at Culloden in 1746.

While the Edinburgh literati usually set themselves apart from the ‘uncivilised’ Highland north, post-Culloden there would have been an awareness that Scottish and Gaelic culture was at best being ‘Anglified’, at worse being stamped out.

The clock was ticking to gather Scottish material before it disappeared forever, and so checks and balances were possibly overlooked.

In a wider British picture, the timing was ripe for rugged tales of Scotland. Since the genuine threat of wild Highlanders had been exterminated and the Highland Clearances were actively underway, Britain was poised to embrace a Romantic view of Highland Scotland, of warriors and lore.

Ossian offered up palatable wild Celts that entertained the readers of the day. Macpherson is commended with sowing the seeds of the Romantic movement itself. Let’s also note that the Ossian works, however they came together, were deemed of such quality that they attracted great minds and admirers, including Thomas Jefferson, and Goethe. Artists, such as Nicolai Abildgaard, Jean-Auguste -Dominique Ingres and Girodet, were inspired by Ossian to put brush to canvas. Hoax or not, the Ossian works had an inherent worth of their own, and their artistic legacy is rich.

It’s also important to analyse the character of Macpherson, to understand more. James grew up close to Ruthven Barracks (a British army fort), in the shadow of Culloden, where the Jacobite cause was crushed – he was just 10 years old when the Jacobites fell.

Growing up surrounded by such bloodshed must have left its mark. Those around him who’d stood up for what was ‘right’ had been brutally cut down on the battlefield or during reprisals. Where did being brave and heroic get you, if not six feet under? To say his moral compass may have been skewed is an understatement.

At the time of the alleged hoax, Macpherson was relatively young and perhaps eager to please. Youth doesn’t excuse a global hoax, but it’s surprisingly easy for situations to spiral out of control when a young outsider is attempting to please the establishment. Equally, growing up near a battlefield where life was cheap (1,300 men fell at Culloden in less than an hour), James may have felt that opportunities must be grasped whether they were moral or immoral.

Lastly, before Ossian, James Macpherson was a nobody. In a time when social mobility was desperately limited, James opened doors for himself. The money flowed in, enabling him to buy a vast country house in Inverness-shire. He became a Member of Parliament, sired a raft of illegitimate children, and even visited America.

Macpherson certainly does not come across as a particularly nice man – he always ensured he came out on top – but as he relaxed in his luxurious Highland villa, perhaps he considered the life of a rich ‘hoaxer’ as being preferable to that of a morally upstanding outlander’s life of limited means.

Today, the Ossian hoax is still debated, with scholars arguing that Samuel Johnson was so scathing of the notion of a Scottish literary culture and ignorant of oral tradition that his dismissal of James Macpherson’s work was heavy handed.

Arguably, the standard dichotomy of Macpherson being either a hero or a hoaxer is too black and white. If the poems have fake elements to them, then Macpherson comes across as a self-centred individual, who was capable of creating great works of literature. He’s no hero, but he’s contributed significantly more to the world than a mere hoax.

It’s ironic that James Macpherson and Samuel Johnson both lie in the South Transept of Westminster Abbey so they can argue together till eternity. Ultimately, Macpherson ignored the golden rule of storytelling and writing – to never become the story.

Read more:

Herstory: The Real Mary King’s Close celebrates Women’s History Month

SCOTLAND MAGAZINE

Published six times a year, every issue of Scotland showcases its stunning landscapes and natural beauty, and delves deep into Scottish history. From mysterious clans and famous Scots (both past and present), to the hidden histories of the country’s greatest castles and houses, Scotland‘s pages brim with the soul and secrets of the country.

Scotland magazine captures the spirit of this wild and wonderful nation, explores its history and heritage and recommends great places to visit, so you feel at home here, wherever you are in the world.