How the legendary king bided his time before clawing his way to power

MORE FROM SCOTLAND MAGAZINE

“It is, in truth, a humiliating record, and it requires all the lustre of de Brus’s subsequent achievement to efface the ugly details of it.” So said writer Herbert Maxwell in analysing Bruce’s conduct before he was crowned Robert I in 1306. Many during this period depict Bruce as shifty and treacherous, so what was going on? Why did the man who secured the independence of Scotland behave the way he did?

When Alexander III fell off his horse in 1286, he left the infant Margaret as his heir and she died on her way from Norway to be betrothed to the heir of Edward I of England. To prevent civil war between the two leading contenders, the great men of Scotland asked the English king to adjudicate on who should be their next monarch.

As many as 13 men put their names forward. All swore an oath of fealty to Edward. One was a native Scot, Patrick Galithly, a burgess of Perth and grandson of William the Lion, but his father was illegitimate, which knocked him out of the reckoning.

The rest were Anglo-Norman barons, who held lands both north and south of the border. The two that stood out, both with powerful support were John Balliol and Robert de Brus, 5th Lord of Annandale, who was an old man in his late 70s. He was a grandson of David, Earl of Huntingdon, the Lion’s younger brother. He had been declared heir to Alexander II in 1238, but that was extinguished by the birth of Alexander III for whom he had been regent during his minority.

Brus claimed that tanistry was on his side. John Balliol was great grandson of Huntingdon, but by an elder daughter. It was nip and tuck who might be chosen. Feudal primogeniture was yet to be fixed in stone, particularly when it came to succession through women.

By no stretch of the imagination could either man be described as Scottish. Balliol held lands in Scotland, England and France. His connection to Scotland was through his mother, Dervorguilla, who inherited Galloway. Brus was Lord of Annandale and probably the richest man in England with estates in Sussex, Cumberland, Durham, Northumberland, Essex and Ireland. He was Constable of Carlisle Castle. His son had gone to Palestine with Edward I and was often about his court.

The loyalties of such people – trained warriors – were to the advancement of their families, to God and to their feudal superiors, not to countries. They took their oaths of fealty seriously even if they were remarkably comfortable about breaking their word when it suited them. When circumstances changed they would take their oaths all over again. To be king was the supreme prize, the peak of the feudal pyramid.

The Brus family was convinced that they had the rightful claim to the Scots throne, and they had the support of the barons of southern Scotland. Led by his brother-in-law, John Comyn III of Badenoch, Balliol’s allies were in the north. In 1292 Edward chose him and he became John, King of Scots.

The old competitor passed the lordship of Annandale to his son, another Robert, to avoid having to swear fealty to Balliol. This Robert married the Countess of Carrick and, on her death, the earldom devolved on their 19-year-old eldest son, the future king Robert I.

Robert swore fealty to Balliol in 1293 for Carrick, but he was heir to the ancestral estates in England and Ireland for which he owed allegiance to Edward. He knew he was a whisker from the throne but he risked losing everything if he raised the wrath of the English king.

Balliol was humiliated by Edward, treated no better than any other of his vassal nobles. In 1295, he lost power to a council of 12 magnates, who made a treaty with France to support each other against Edward. In 1296 the English king invaded, brutally sacking Berwick, defeating a Scots army at Dunbar and seized the Stone of Scone and the national records. Balliol abdicated and Edward summoned the nobility to swear fealty to him in the Ragman Roll, which they did. He then set up government from Berwick.

William Wallace rose in rebellion the following year, but it was to re-instate Balliol as king. He was joined by Andrew Moray from the north and, in the south west, by Bruce and his powerful supporters. In July 1297, the southern rebellion humiliatingly collapsed in the face of a posse from north England and its participants again swore fealty to Edward.

The Battle of Stirling Bridge came in September and Wallace became Guardian of Scotland. Bruce, again a re-sworn vassal of Edward, was in Carlisle, his father commanding the castle when Wallace wasted northern England in the aftermath. The Comyn faction made it their first task to besiege the Bruces in Carlisle.

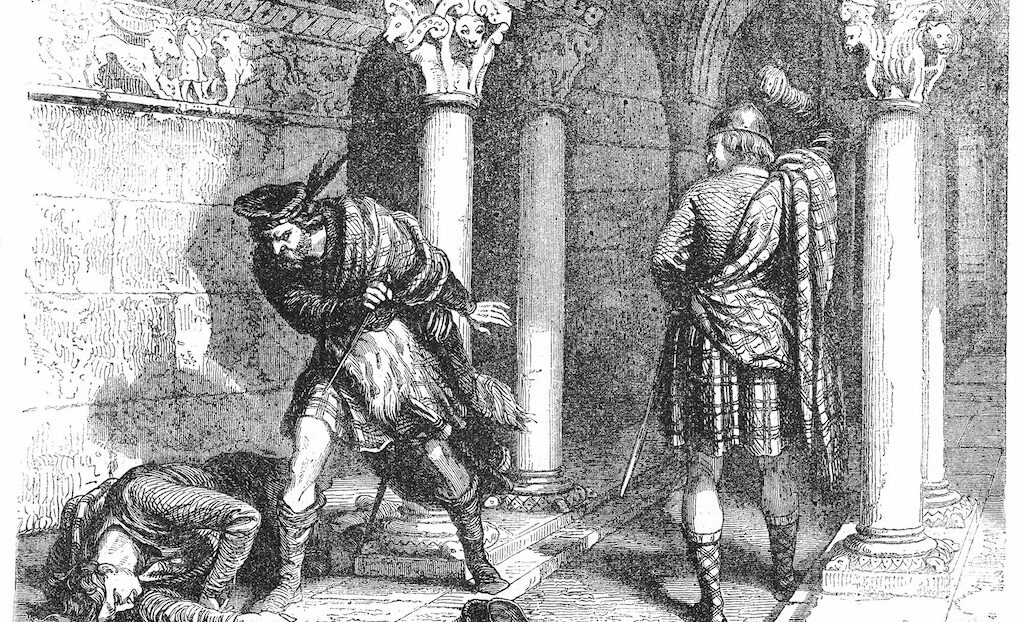

The following spring, Edward brought an army north, defeating Wallace at the Battle of Falkirk. Bruce stayed close to Edward but kept his options open in Scotland. In 1299, along with John Comyn and the Bishop of St Andrews, he was appointed a Guardian when Wallace went abroad to drum up support for his country. At the meeting Comyn and Bruce, the same age and both with inherited claims to the throne, had an altercation – Bruce was grabbed by the throat.

Over the next few years, Bruce ostensibly stayed close to Edward. His father died and he swore fealty for his lands in England. Finally, in 1304 Edward crushed the remnants of rebellion and the Scots nobles once more swore fealty. Abandoned, Wallace was executed in London in 1305.

Read the full feature in the September/October 2020 issue of Scotland.

Read more:

MORE FROM SCOTLAND MAGAZINE

SCOTLAND MAGAZINE

Published six times a year, every issue of Scotland showcases its stunning landscapes and natural beauty, and delves deep into Scottish history. From mysterious clans and famous Scots (both past and present), to the hidden histories of the country’s greatest castles and houses, Scotland‘s pages brim with the soul and secrets of the country.

Scotland magazine captures the spirit of this wild and wonderful nation, explores its history and heritage and recommends great places to visit, so you feel at home here, wherever you are in the world.